NPR recently did a report on “robo-grading” of student essays via computer for standardized tests and other constructed responses. It’s a growing field in which proponents have touted advancements in artificial intelligence and savings of time and money.

Developers of so-called “robo-graders” say they understand why many students and teachers would be skeptical of the idea. But they insist, with computers already doing jobs as complicated and as fraught as driving cars, detecting cancer, and carrying on conversations, they can certainly handle grading students’ essays.

“I’ve been working on this now for about 25 years, and I feel that … the time is right and it’s really starting to be used now,” says Peter Foltz, a research professor at the University of Colorado, Boulder. He’s also vice president for research for Pearson, the company whose automated scoring program graded some 34 million student essays on state and national high-stakes tests last year. “There will always be people who don’t trust it … but we’re seeing a lot more breakthroughs in areas like content understanding, and AI is now able to do things which they couldn’t do really well before.”

Foltz says computers “learn” what’s considered good writing by analyzing essays graded by humans. Then, the automated programs score essays themselves by scanning for those same features.

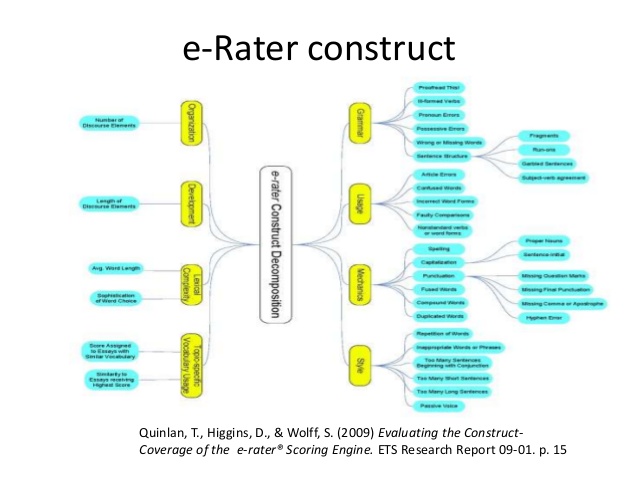

“We have artificial intelligence techniques which can judge anywhere from 50 to 100 features,” Foltz says. That includes not only basics like spelling and grammar, but also whether a student is on topic, the coherence or the flow of an argument, and the complexity of word choice and sentence structure. “We’ve done a number of studies to show that the scoring can be highly accurate,” he says (https://www.npr.org/2018/06/30/624373367/more-states-opting-to-robo-grade-student-essays-by-computer).

If you look at Foltz’s job title, you will see that he works for Pearson. It would not take very long to research the relationship that North Carolina has with Pearson. It’s rather complicated.

The idea that a student’s written response could be graded by a computer is hard to fathom for this AP English teacher. If there is any language that colorfully deviates from a linear construction of putting words together with words from the world’s most vast lexicon, it’s English.

One can see how grammar, usage, and mechanics could be “screened” by a computer program. But voice, syntax, language, tone, diction, imagery, figurative language. Graded by a computer?

Several states including Utah and Ohio already use automated grading on their standardized tests. Cyndee Carter, assessment development coordinator for the Utah State Board of Education, says the state began very cautiously, at first making sure every machine-graded essay was also read by a real person. But she says the computer scoring has proven “spot-on” and Utah now lets machines be the sole judge of the vast majority of essays. In about 20 percent of cases, she says, when the computer detects something unusual, or is on the fence between two scores, it flags an essay for human review. But all in all, she says the automated scoring system has been a boon for the state, not only for the cost savings, but also because it enables teachers to get test results back in minutes rather than months.

Money. Time. Savings.

That’s a recipe that the North Carolina General Assembly would like and they sure would not mind going through Pearson to do it. In a state that houses some of the best departments of teacher education in the South and has a university system rife with technology and learning, it would make sense for a state government that controls the state superintendent’s office to go to a private entity to not spend money on authentic grading.

It’s just their way.

Peter Green, a veteran educator and writer who also has a great blog called Curmudgucation, wrote a piece on robo-grading for Forbes this month called “Automated Essay Scoring Remains an Empty Dream” (https://www.forbes.com/sites/petergreene/2018/07/02/automated-essay-scoring-remains-an-empty-dream/#3f6c594b74b9).

He writes,

…but the basic problem, beyond methodology itself, was that the testing industry has its own definition of what the task of writing should be, which more about a performance task than an actual expression of thought and meaning. The secret of all studies of this type is simple– make the humans follow the same algorithm used by the computer rather than he kind of scoring that an actual English teacher would use. The unhappy lesson there is that the robo-graders merely exacerbate the problems created by standardized writing tests.

The point is not that robo-graders can’t recognize gibberish. The point is that their inability to distinguish between good writing and baloney makes them easy to game. Use some big words. Repeat words from the prompt. Fill up lots of space. Students can rapidly learn performative system gaming for an audience of software. And the people selling this baloney can’t tell the difference themselves. That’s underlined by a horrifying quote in the NPR piece. Says the senior research scientist at ETS, “If someone is smart enough to pay attention to all the things that an automated system pays attention to, and to incorporate them in their writing, that’s no longer gaming, that’s good writing.”

In other words, rather than trying to make software recognize good writing, we’ll simply redefine good writing as what the software can recognize.

Computer scoring of human writing doesn’t work. In states like Utah and Ohio where it is being used, we can expect to see more bad writing and more time wasted on teaching students how to satisfy a computer algorithm rather than develop their own writing skills and voice to become better communicators with other members of the human race. We’ll continue to see year after year companies putting out PR to claim they’ve totally got this under control, but until they can put out a working product, it’s all just a dream.

He’s right.

You just can’t automate voice.

Makes one think if this is the direction for North Carolina on a large scale because there are many in Raleigh who do not want people to develop voice.

Six years ago, one of our assistant principals having attended a summer workshop for administrators, approached me with an offer from “Robo-grading” program (online) that was in testing. Would be interested in beta-testing the system and then talking with the developers.

I said yes.

After six months, I quit explaining that other than counting words as the means of determining if a paragraph was sufficiently developed, spelling, punctuation, and few simple style elements, the program evaluation was useless.

It could tell the difference between active and passive voice , but had no idea which mode was appropriate to the the subject/ genre. The same was true of lexile.

But when it came to determining the most advantageous POV, subtleties of irony, or humor, the program was “tone deaf.”

The highest values were awarded to utterly wooden, formulaic written expression devoid of any insightful thinking.

When I attempted to explain this to a student who received the grade, my explanation was met with hurt feelings because the teacher was overriding the A with a C-.

That was not an experience I wanted to repeat.

Has anyone looked to how much money Pearson is giving to the legislators supporting mechanical grading. I suspect therein lies another story.

LikeLike